On a still evening near Wellington, 15 kilometres east of Dubbo, the turbines of the Bodangora Wind Farm turn slowly against a fading sky [1]. For locals, they’re both a symbol of change and a reminder of the debate that refuses to die. Across Australia, conversations about climate and the energy transition still divide dinner tables and political party rooms alike.

Yet beneath the noise lies a simple truth: Australia’s prosperity and security now depend on how well we manage this transition — not whether we believe in it.

The facts, not the fight

Since 1910, Australia’s average surface temperature has risen about 1.3°C, slightly above the global mean [2]. The result is a sharp rise in extreme heat, fire danger and flood losses — impacts that appear not in ideology but in insurance bills and emergency budgets.

The Insurance Council of Australia estimates that climate-related disasters already cost the nation $4.5 billion a year, and rise almost 10-fold by 2050 without stronger mitigation and adaptation [3].

Regional and rural communities are already bearing a rising share of these climate-hazard losses. Insurers are withdrawing from high-risk regions, making parts of northern NSW and Queensland nearly uninsurable. These are today’s livelihood and balance-sheet losses, not distant hypotheticals.

The practical question is clear: how do we deliver reliable, affordable, Australian-made energy while cutting the social, physical and financial risks of an unstable climate?

The smart path forward

The evidence from the CSIRO and AEMO is unequivocal [4]. The least-cost, most reliable way to replace ageing coal stations is a system built on renewables + storage + modern transmission, with flexible gas for backup. That’s not ideology; it’s engineering and economics.

Furthermore, the latest IEA World Energy Outlook [5] underscores that many developed nations are already finding renewables and efficiency the cheapest route to energy security and decarbonisation – so long as policy certainty is assured and infrastructure can be delivered in a timely way.

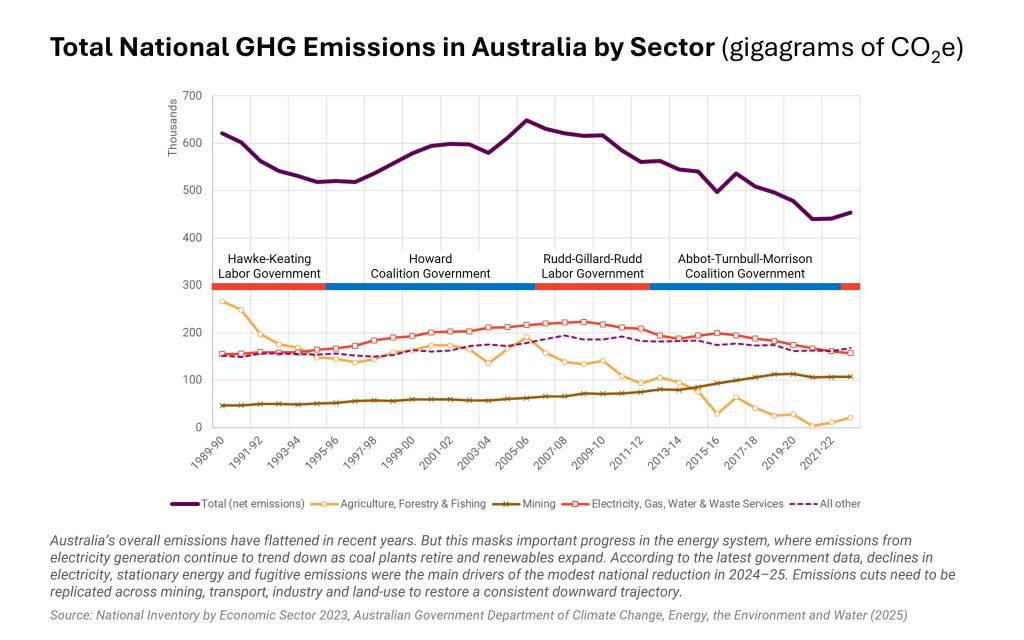

What Australia does matters

Some argue that our emissions — just over 1 % of the global total — are too small to matter. But Australia is also one of the world’s largest fossil-fuel exporters, and when our coal and gas are burned overseas they add roughly 3–4 % of global emissions [6]. We also remain among the highest per-capita emitters in the developed world.

Beyond that arithmetic lies influence. Global markets are shifting fast: Japan, Korea and the EU are embedding carbon-border tariffs and clean-supply standards [7]. Falling behind risks our competitiveness, investment flows and national reputation.

Our share may be small, but the cost of inaction is large — and local.

Sovereign energy security matters too

In a more fractured and contested Indo-Pacific, Australia’s most sensible and robust energy strategy is one that maximises domestic, distributed and electrified supply while sharply reducing dependence on imported liquid fuels.

Air Vice-Marshal (Ret’d) John Blackburn AO captures the vulnerability bluntly: “Australia is the least energy-secure nation in the developed world… we have outsourced our energy security to global supply chains we do not control” [8]. With more than 90% of our refined fuels imported, he warns that “a disruption to maritime supply routes would see essential services fail within weeks” [9].

This is why a high-renewables, storage-backed, transmission-connected electricity system—supported by domestic gas for firming, strategic liquid-fuel reserves, diversified supply chains, electrified transport, and microgrids for critical infrastructure—is not only the lowest-cost energy pathway, but also the most resilient in a crisis.

Australia’s place in the world

Australia has long punched above its weight as a middle power — from regional peacekeeping to trade liberalisation and global health. When Australia acts with competence and fairness, others notice.

If we manage the energy transition well, we reinforce that reputation for practical leadership. If we falter, we erode both credibility and economic opportunity.

Our voice matters not because of volume, but because of trust rooted in delivery.

The accelerating revolution underway

Technology transitions don’t move in straight lines. Solar, wind and batteries are following an S-curve — slow at first, then rapid uptake and cost collapse.

In just two decades, solar module prices have fallen over 90%, while lithium-ion batteries are down about 85% [10].

Every megawatt built today accelerates that curve. Early investment shortens the hump in prices; delay lengthens it. Acting early isn’t a cost — it’s a dividend waiting to be claimed.

The nuclear question: open-minded, not distracted

Some call nuclear the answer. And, yes, Australians should remain open minded to its use, but facts matter.

The CSIRO GenCost 2023-24 report finds nuclear generation would cost two-to-four times more and take 10–15 years longer to deliver than renewables + storage [11]. Other independent studies support this finding.

The Climate Change Authority also estimates a nuclear pathway would add roughly 1 billion tonnes CO₂ to 2050 compared with the renewable route [12].

Nuclear may have a role later; today it would delay progress and drive up bills.

What about coal-fired power with CCS?

Carbon capture and storage (CCS) remains unproven at commercial scale for coal-fired power anywhere in the world.

Demonstration projects in Canada and the United States have run far below design capacity and have not been economically viable without heavy subsidies [13]. Scaling CCS for coal would require massive new infrastructure and would still produce electricity far more expensive than renewables and storage [14,15].

By the time the technology could hypothetically mature, most of Australia’s coal fleet will already have closed. CCS may play a role in hard-to-abate industries, but it is not a realistic or cost-effective pathway for Australia’s electricity system [16].

Why power prices are high — and why they’ll fall

Australians are weary of high power prices. The causes are plain:

- the cost of enacting the energy transition after two decades of policy delay,

- exposure to volatile global gas and coal prices, and

- ageing coal plants failing more often.

If current transition plans are delivered on schedule, the AEMC projects average household bills could fall ≈ 13 % by 2034 [17]. Furthermore, households that electrify appliances and cars can realise much larger savings through the benefits of lower gas and petrol prices. So, if we hesitate or abandon net-zero by 2050, costs stay high and investors retreat.

Ten years to cheaper, sustainable Australian energy if we hold our nerve and support people through the transition.

Fairness first

The transition must feel fair to succeed:

- renters and low-income households need access to technology upgrades,

- small manufacturers need predictable prices, and

- regional Australians must share the upside.

Community energy hubs, rental-efficiency standards and local ownership models, for example, translate policy into fairness. And fairness isn’t sentiment — it’s economic glue.

Regions: the new energy heartland

Most renewable and storage projects will rise in regional Australia. Handled well, this can be the next great regional development story: billions in investment, lease income for farmers, long-term service jobs and revitalised towns. Handled poorly, it will deepen division. So, regional leadership — not mere consent — is essential.

Protecting what we love while we build what we need

Some of the best renewable zones overlap with sensitive landscapes. That’s a challenge, not a reason to stop.

By prioritising cleared land, improving spatial mapping and strengthening biodiversity protections and offsets, we can protect ecosystems and build responsibly.

Clean energy and environmental stewardship can, and must, progress together.

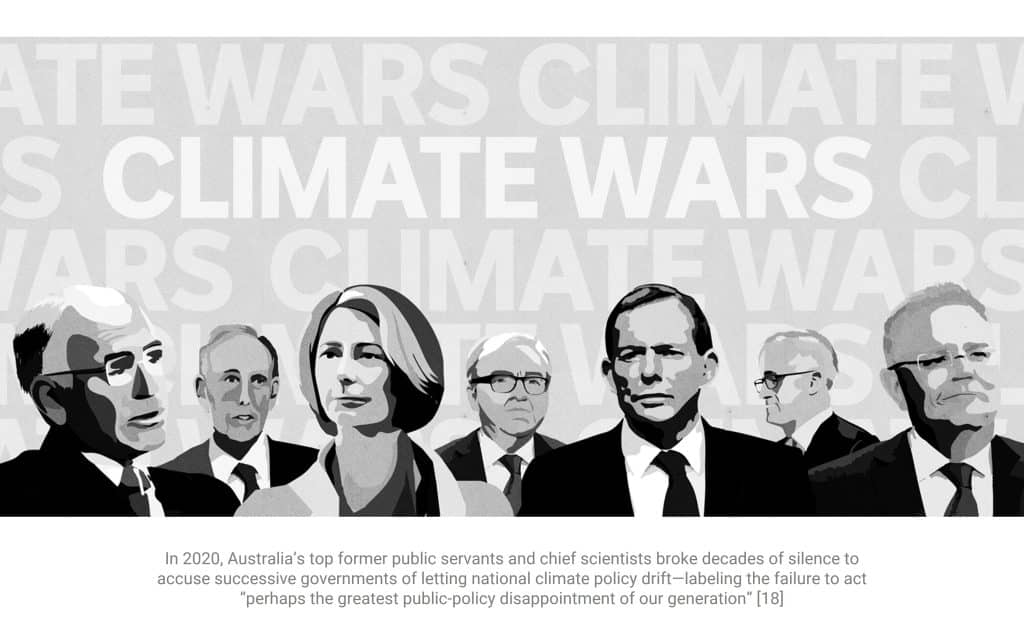

The politics we can no longer afford

Twenty years of climate wars drove up costs and delayed investment.

Today, as the Liberal-National Coalition drops its commitment to the net-zero by 2050 target, we should remember: instability raises borrowing costs, scares off capital and damages confidence in Australian governance.

Abandoning net zero would not lower bills; it would lock in uncertainty, lost opportunity, and further erode trust in politics and democratic institutions.

What leadership looks like now

True leadership isn’t about comfort. It means staying the course when the task is hard and the rewards distant.

Leaders in government, business and community must:

- Lock in stable, bipartisan frameworks so capital flows.

- Design projects with communities.

- Deliver transmission and storage projects on time and transparently.

- Guarantee fairness and regional benefit.

- Treat environmental integrity as non-negotiable.

- Speak honestly — no slogans, no scare campaigns.

The call to courage

Australia didn’t build the Snowy Scheme, the NBN or its world-class resources industry because they were easy. We built them because they were necessary. The energy transition demands the same resolve.

Those who lead it — from all sides — won’t just secure cheaper, cleaner power; they’ll define what responsible Australian leadership looks like in an age of disruption.

History will not remember who argued loudest. It will remember who secured the right to govern, and exercised it wisely.

References

[1] Bodangora Wind Farm – Infigen Energy (now Iberdrola Australia), Project Profile: https://www.infigenenergy.com/our-assets/asset-map/operating-renewable-energy-assets/bodangora

[2] CSIRO & Bureau of Meteorology (2024) State of the Climate 2024, Commonwealth of Australia, Canberra.

[3] Insurance Council of Australia (2022) Building a more resilient Australia: Policy proposals for the next Australian Government, Sydney.

[4] AEMO (2024) 2024 Integrated System Plan, Melbourne.

[5] IEA (2025) World Energy Outlook 2025, 12 November 2025, International Energy Agency, Paris.

[6] Hannah Grant, Bill Hare (2024) Australia’s global fossil fuel carbon footprint, Climate Analytics, Perth.

[7] European Commission (2023) Carbon Border Adjustment Mechanism briefing.

[8] Amy Sarcevic (2020) Australia needs a military approach to liquid fuel security – John Blackburn AO, 7 Oct 2020, Informa Insights.

[9] James Bowen (2025) Full Tanks, Full Batteries: Enhancing Australia’s Short- and Long-Term Energy Security, Black Swan Strategy Paper, Issue 15, August 2025.

[10] IEA (2024) Renewables 2023: Analysis and forecasts to 2028, International Energy Agency, January 2024, Paris.

[11] Paul Graham, Jenny Hayward and James Foster (2024) GenCost 2023‐24: Final report, CSIRO, Canberra.

[12] Climate Change Authority (2025) Assessing the impact of a nuclear pathway on Australia’s emissions, Commonwealth of Australia, Canberra.

[13] IEA (2024) Accelerating Just Transitions for the Coal Sector: Strategies for rapid, secure and people-centred change, International Energy Agency, Paris.

[14] IEA, Carbon Capture Utilisation and Storage overview: https://www.iea.org/energy-system/carbon-capture-utilisation-and-storage

[15] Paul Graham, Jenny Hayward and James Foster (2025) GenCost 2024-25: Final report, CSIRO, Canberra

[16] Tom Monaghan (2024) Carbon Capture Storage – A viable option for Australia’s future? Australian Energy Council, Melbourne

[17] AEMC (2024) Residential Electricity Price Trends 2024, Australian Energy Market Commission, Sydney.

[18] Michael Brissenden (2020) Australia’s most senior former public servants and scientists reveal their anger about climate policy failure, ABC ‘Four Corners’, 18 May 2020